GETTY IMAGES

GETTY IMAGES

As India and Pakistan celebrate 70 years of independence, Andrew Whitehead looks at the lasting legacy of the Partition of British India, and the turmoil and trauma which marred the birth of the two nations.

It's about 700km (430 miles) from Delhi to Islamabad - less than the distance between London and Geneva. A short hop in aviation terms.

But you can't fly non-stop from the Indian capital to the Pakistani capital. There are no direct flights at all. It is only one of the legacies of seven decades of mutual suspicion and tension.

Take another example: cricket.

India and Pakistan played each other a few weeks ago in the final of the Champions' Trophy. Both countries are cricket crazy.

Partition of India in August 1947

- Perhaps the biggest movement of people in history, outside war and famine.

- Two newly-independent states were created - India and Pakistan.

- About 12 million people became refugees. Between half a million and a million people were killed in religious violence.

- Tens of thousands of women were abducted.

- This article is the first in a BBC series looking at Partition 70 years on.

However, the game was played not in South Asia, but in London. India and Pakistan don't play cricket in each other's countries any more, although they have met in one-day matches around the world, including in countries in their region like Bangladesh and Sri Lanka.

GETTY IMAGES

GETTY IMAGES

But it is almost 10 years since they faced each other on South Asian soil in a Test match. Despite a lot of shared culture and history, they are not simply rivals, but more like enemies.

In the 70 years since India and Pakistan gained independence, they have fought three wars. Some would say four, although when their armies last fought in 1999, there was no formal declaration of war.

The simmering tension between India and Pakistan is one of the world's most enduring geopolitical fault lines. It has prompted both countries to develop their own nuclear weapons.

So the uneasy stand-off is much more than a regional dispute: it is fraught with wider danger.

GETTY IMAGES

GETTY IMAGES

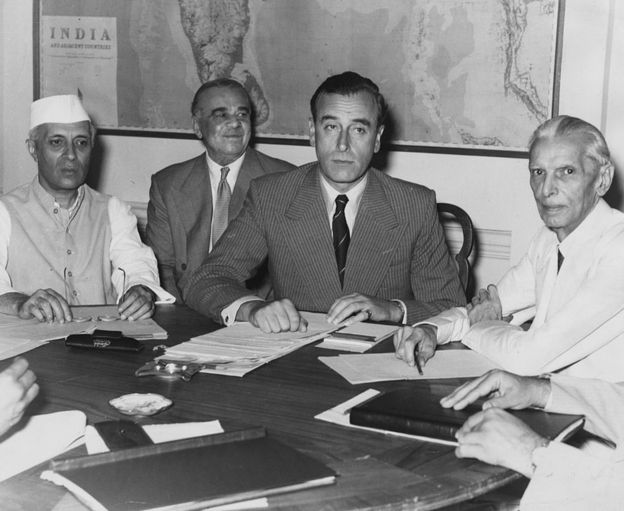

India and Pakistan gained their independence at the same moment. British rule over India, by far its biggest colony, ended on 15 August 1947.

After months of political deadlock, Britain agreed to divide the country in two.

A separate and mainly Muslim nation, Pakistan, was created to meet concerns that the large Muslim minority would be at a disadvantage in Hindu-majority India.

This involved partitioning two of India's biggest provinces, Punjab and Bengal. The details of where the new international boundary would lie were made public only two days after independence.

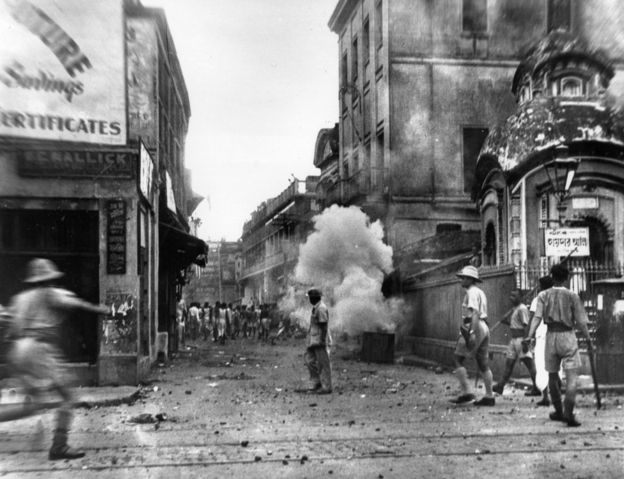

Partition triggered one of the great calamities of the modern era, perhaps the biggest movement of people - outside war and famine - that the world has ever seen.

No one knows the precise numbers, but about 12 million people became refugees as they sought desperately to move from one newly independent nation to another.

GETTY IMAGES

GETTY IMAGES

Amid a terrible slaughter in which all main communities were both aggressors and victims, somewhere between half a million and a million people were killed.

Tens of thousands of women were abducted, usually by men of a different religion.

In Punjab in particular, where Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs had lived together for generations and spoke the same language, a stark segregation was brought about as Muslims headed west to Pakistan and Hindus and Sikhs fled east to India.

GETTY IMAGES

GETTY IMAGES

This was not a civil war with battle lines and rival armies - but nor was it simply spontaneous violence.

On all sides, local militias and armed gangs planned how to inflict the greatest harm on those they had come to see as their enemies.

GETTY IMAGES

GETTY IMAGES

Those wounds have been left to fester. No one has been held to account - there's been no reconciliation process - and for a long time, the full story of what happened has been smothered in silence.

Literature and cinema found ways of representing the horror of what happened. Historians initially focused on the politics of Partition. It took them much longer to turn their attention to the lived experience of this profound rupture.

Big oral history projects have got under way only in the last few years, as the number of survivors dwindles. There are no towering memorials to the Partition dead.

The first museum devoted to Partition opened in 2016 in Amritsar in Indian Punjab.

Partition poisoned relations between India and Pakistan, and has shaped - many would say distorted - the geopolitics of South Asia as a whole.

Pakistan initially consisted of two wings 2,000km (1,240 miles) apart, but in 1971, East Pakistan gained its independence, with Indian military support. Another new nation, Bangladesh, was born.

GETTY IMAGES

GETTY IMAGES

Among the loose ends of the independence arrangement was the future of Kashmir, a princely state in the foothills of the Himalayas which had a largely Muslim population. The maharaja, a Hindu, decided his state should become part of India.

Within months, Indian and Pakistani troops were fighting each other for control of Kashmir.

The complex conflict remains unresolved and, more than any other issue, has bedevilled relations between the two countries.

India also accuses Pakistan of supporting militant organisations which have carried out terrorist-style attacks in Indian cities. Pakistan says India colludes with breakaway movements in areas such as Balochistan.

The political leaders of the two countries have met from time to time. There have been occasional hopes of a breakthrough in relations but, at the moment, relations are distinctly frosty.

GETTY IMAGES

GETTY IMAGES

The consequences have been far-reaching.

India has much more trade with countries such as Nigeria, Belgium or South Africa than with its neighbour to the west.

Although India's phenomenally successful Hindi-language film industry - known as Bollywood - is hugely popular in Pakistan, and Pakistan's TV soaps are eagerly watched in India, cultural links are fragile.

When tensions rise, which they do regularly, every aspect of relations suffers.

GETTY IMAGES

GETTY IMAGES

Just a few months ago, one of India's leading film directors Karan Johar felt obliged to promise that he would never again cast a Pakistani actor in one of his movies.

The two countries are not well informed about what is happening on the other side of the border. No major Indian or Pakistani news organisation currently has a correspondent in the other country's capital.

For both Indians and Pakistanis, travelling to the other country is not easy - even if it is to visit family.

It is not the difficulty of getting a visa or the lack of direct flights between the two capital cities. There are very few air links between the two countries at all.

GETTY IMAGES

GETTY IMAGES

Despite a lengthy shared border, India and Pakistan have hardly any border crossings.

In Pakistan, the army and its intelligence wing are by far the most powerful institutions - and the country has had repeated spells of military rule.

The abiding sense of a military threat from its much larger neighbour has - many feel - boosted the power of the armed forces and hindered the development of a mature democracy.

Pakistan has a population of about 200 million - mostly Muslims. India has almost 1,300 million citizens and about one in seven follow Islam. There are almost as many Indian Muslims as Pakistani Muslims.

One projection suggests that by 2050, India will overtake Indonesia to become the country with the world's biggest Muslim population. But Muslims are under-represented in India's parliament and many other areas of public life.

Some observers believe the perception - however unfair - that Indian Muslims sympathise with Pakistan has fed prejudice and discrimination.

REUTERS

REUTERS

The pride that almost all Indians and Pakistanis feel about their nation is self-evident. Patriotism is a powerful force in both countries.

It is on public display every time they play each other at cricket. But both have been unable to overcome the legacy of the tragedy which accompanied what should have been their finest moment 70 years ago.

And the result of their most recent tussle on the cricket pitch? Well, for the record, Pakistan won a surprise - and emphatic - victory.

Some in India were gracious in defeat. But on social media, and some sections of India's news media, there was anger and anguish - losing face to your old rival remains, for many, almost too painful to endure.

About this piece

This analysis was commissioned by the BBC from an expert working for an outside organisation.

Dr Andrew Whitehead is a former BBC India correspondent. He is the author of a book about Kashmir in 1947 and is currently honorary professor at the University of Nottingham.

No comments:

Post a Comment